You must have heard these headlines: “Electric Vehicles are the future!” “Go green, drive electric!” But one question might bother you—if making an EV battery requires so much mining and energy, is it actually cleaner? Or is it just an additional burden after non-EV automobiles? And seeing your neighbour buys an electric car but keeps his old diesel SUV, is that really progress, or just adding another vehicle to the road?

1. The “Carbon Load” – Why Building an EV is Energy-Intensive

Imagine that every car is built with a hidden “carbon load” along with all the pollution released during its manufacture. For an Electric Vehicle (EV), this backpack is heavier right from the factory gate.

Why? The Battery.

The main component of an EV is its massive lithium-ion battery. The process of making it involves:

- Mining: Deep digging up lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite from the earth. This process is energy-intensive and can cause local environmental damage. Large, diesel-powered machinery is used for blasting, crushing, and transporting massive amounts of soil and rock. The combustion of diesel fuel releases a significant amount of carbon dioxide and other pollutants. These facilities often use electricity from fossil fuel-heavy grids, particularly in countries such as China (the world's largest battery production hub) and India.

- Processing & Manufacturing: Refining those materials and assembling the battery in high-tech, high-power-consumption factories.

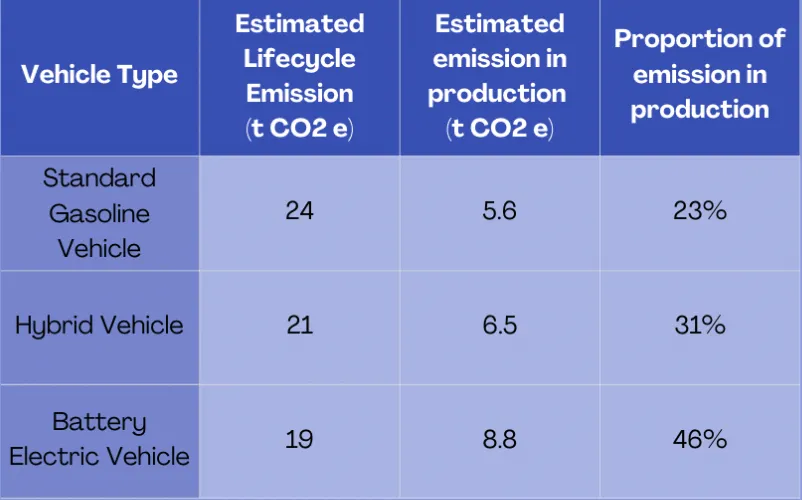

Studies show that manufacturing a typical EV battery today results in significantly more greenhouse gas emissions than manufacturing an engine and transmission for a petrol or diesel car. However, their total lifecycle emissions are considerably lower than those of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Some estimates suggest the EV starts its life with a 30-40% larger “carbon load.”

Producing one tonne of lithium (enough for ~100 car batteries) requires approximately 2 million tonnes of water, which makes battery production an extremely water-intensive practice.

So, is the viral claim true? Yes, at the manufacturing stage, producing an EV generally creates more emissions than producing a conventional car. The EV begins its life with a carbon debt.

The EV starts with a heavier "carbon backpack. Manufacturing an EV battery = higher initial emissions.

Source : Based on: 2015 vehicle, 150k KM usage, 10% ethanol blend, 500g/KWH grid electricity

2. The Lifelong Race: When Does the EV “Break Even”?

But here is a twist. A car’s total environmental impact isn’t just about its birth, but also you have to keep calculating its entire life, from manufacturing to its destruction.

Think of it this way:

- Petrol/Diesel Car: It’s made with a relatively lower carbon load, but it has a leaky fuel tank. For its entire life (10-15 years), it constantly burns fuel, emitting carbon dioxide (CO₂) directly out of its tailpipe. That leak never stops.

- Electric Vehicle: It’s born with a heavier load, but it has no tailpipe. Its “fuel tank” is its battery, which gets refilled with electricity.

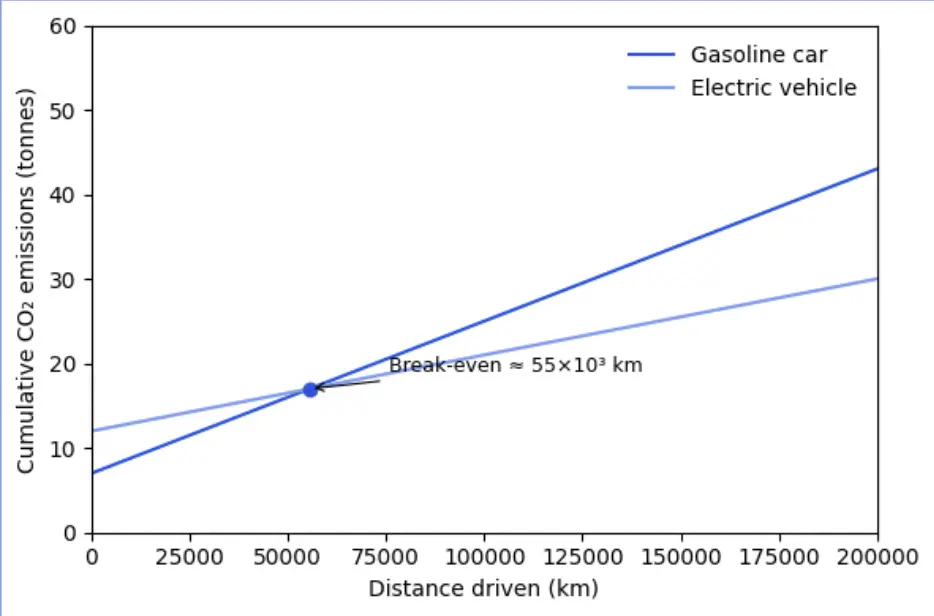

An EV's total lifetime emissions become lower than a petrol car after about 35,000 - 70,000 miles of driving. This is the "break-even point."

Break-Even Is Not a Constant. It varies with grid intensity and manufacturing emissions. Break-even will be achieved earlier if clean grid is use for EV-charging as cleaner battery manufacturing shifts the break-even point to lower grid intensities.

The most crucial question: Where does that electricity come from?

- Scenario A: A Coal-Powered Grid (Like much of India’s electricity today): Charging the EV is like filling its battery with coal smoke. It still causes pollution, but at the distant power plant. Because power plants and EVs are both more efficient than small petrol engines, an EV on a coal-heavy grid still ends up causing less total lifetime emissions than a petrol car. It takes a few years of driving to “pay off” its manufacturing carbon debt, but it gets there.

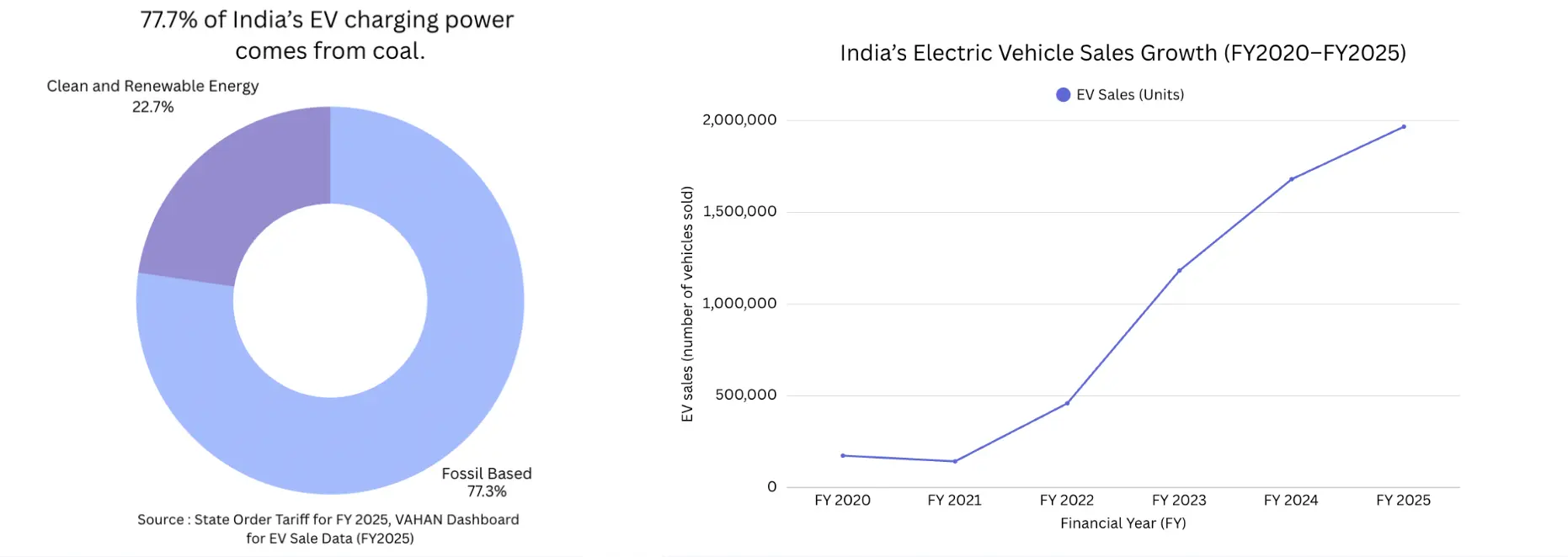

India's EV sales grew 11 times in just 5 years (2020 to 2025). That's huge growth! But right now, only 22.3% of the electricity used to charge these EVs comes from clean sources like sun, wind, and water. The rest (over 77%) comes mainly from coal.

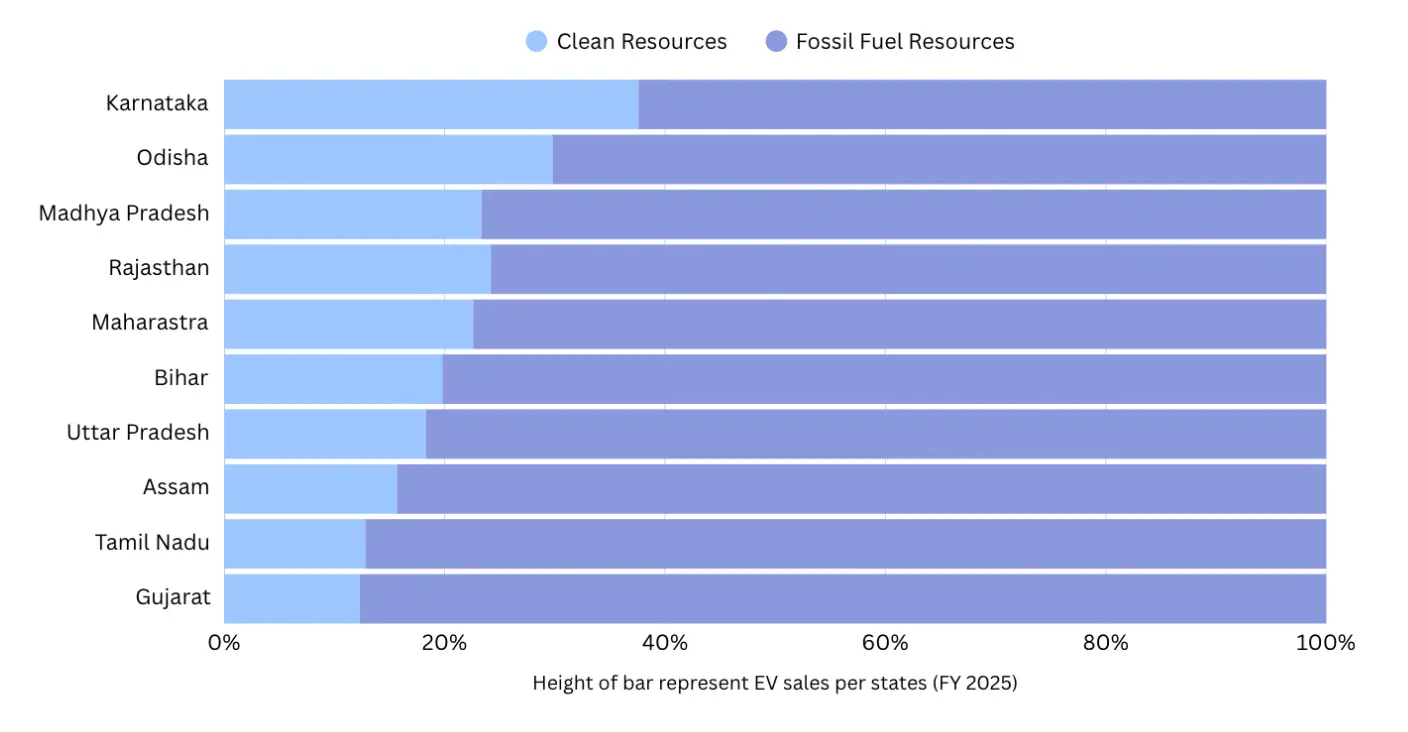

For FY2025, Karnataka led with 37.6% of electricity mix coming from solar, wind and hydro, providing the cleanest charging option for EVs. Odisha (29.8%) and Assam stood out with a significant share of hydro, whereas Rajasthan (24.2%) and Madhya Pradesh (23.8%) have relatively higher wind and solar shares. In contrast, solar and wind resource-rich states (with limited hydro capacity), like Gujarat (12.3%) and Tamil Nadu (12.8%), have a limited share of clean electricity to supply to EVs.

Source : From fossil to flexible: Advancing India’s road transport electrification, 2025 report by Energy Ember.

- Scenario B: A Renewable-Powered Grid (The Goal): Charging the EV with solar, wind, or hydro power is like filling its battery with sunshine or wind. After paying off the initial manufacturing debt, the EV’s lifetime emissions plummet to a fraction of those of a petrol car.

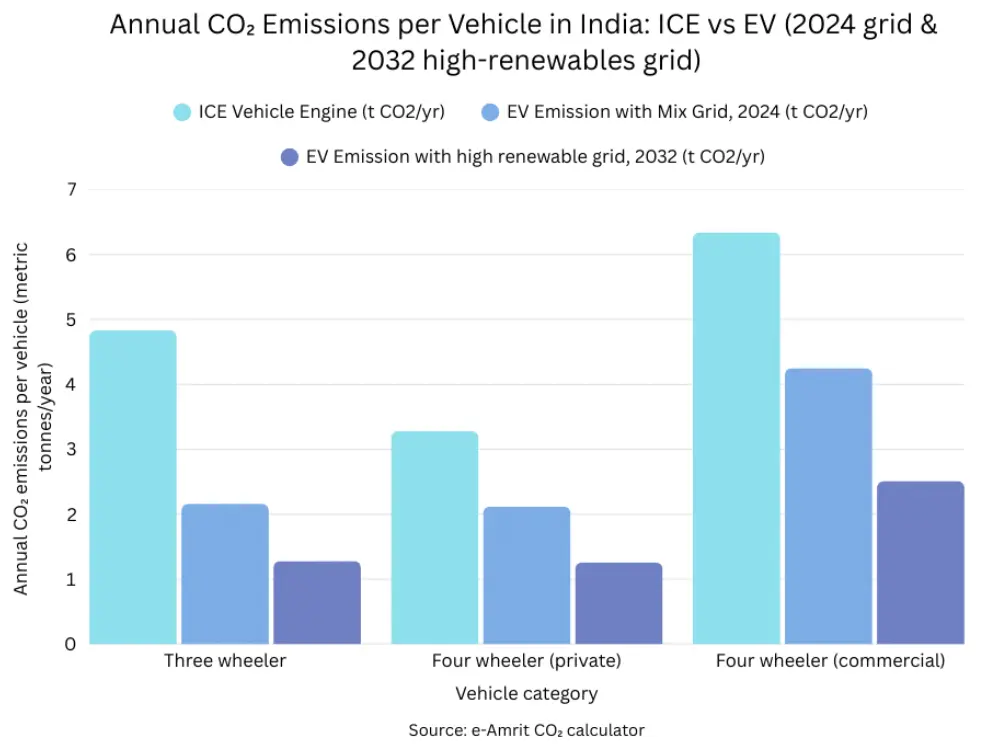

Transition from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to EVs can cut emissions by 33%-55%. These emissions can be reduced further by moving away from fossil fuel-based electricity resources to clean electricity resources.

The Verdict: In reality, over its entire lifetime, an EV will be responsible for fewer emissions than a petrol/diesel car. The “break-even” point can be anywhere from 15,000 to 70,000 km, depending on the grid. As grids become cleaner, we can get more benefit from the cleaner results of EVs.

3. The “Additional” vs. “Substitute” Dilemma – The Indian Reality

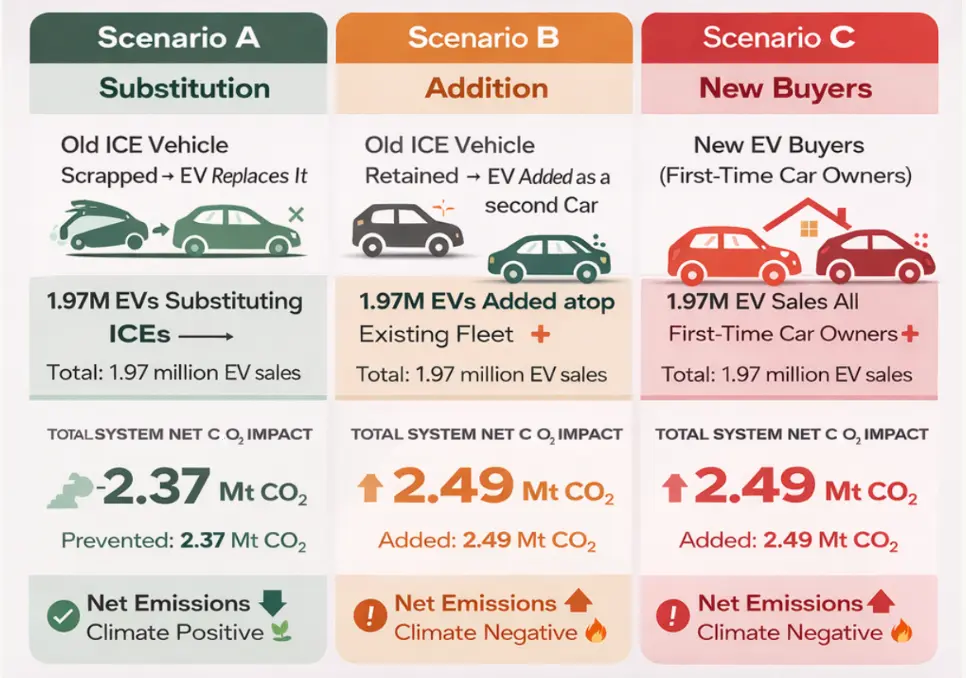

This is the most crucial question to ask and notice, which is often ignored during planning and implementation. The climate math above assumes one EV directly replaces one petrol car. But is the same happening in developing nations, especially in India?

The Theory (What Ideal Models Assume): If an old, polluting car is scrapped and replaced by a new & cleaner EV, the number of net vehicles on the road remains the same, while pollution is supposed to be mitigated.

Meanwhile, On-Ground Reality (What Often Happens in Growing Economies like India):

- The “Second Car” Family: A family buys a compact EV (like a Tata Nexon EV) for daily office commutes and short city rides. But they keep their older, larger petrol SUV for weekend trips, outstation travel, or because of “range anxiety.” As a result, the household now has two cars instead of one. The total manufacturing emissions have increased (one new EV and one old ICE), and while daily city pollution may decrease, the system-wide burden rises.

- First-Time Buyers in a Growing Market: For millions, an EV isn’t replacing a car; it’s their first-ever car. This is an addition, not a substitution, adding to the total number of vehicles.

EV deployment without parallel ICE retirement can increase total system emissions in high-growth markets, despite purely clean grid. Most EV analyses assume replacement. We quantify what happens when that assumption fails.

In the short term, for many Indian households, an EV feels more like an “additional” burden on the system than a clean substitute. We are not consistently subtracting the tailpipe emissions of retired ICE vehicles at the same rate as the manufacturing emissions of new EVs.

4. Failure Of Ethanol Blending Scheme in India: A "Green" Solution That Fueled an Industry, Not a Revolution

Following the discussion of drawback of implementing EV, India recently adopted another "green" fix for petrol cars: Ethanol Blending. The government pushed to mix ethanol (made from sugarcane) with petrol, aiming for E20 (20% ethanol) by 2025 —promising less pollution, lower oil imports, and more money for farmers.

But we are getting opposite and unfavourable results from what we were expecting for the last 5 years. Let's see what the real story of ethanol holds crucial lessons for today's EV debate.

4.1 Higher GHG Emission

Growing enough sugarcane for fuel requires massive amounts of water and chemical fertilizers, harming water sources and soil, and creating possible instability in food security in the long term. Crucially, studies found that burning high-ethanol fuel (like E20) in many cars can actually release more of certain harmful pollutants than regular petrol. This means the air in our cities might not get cleaner—it could even become more toxic for our lungs.

Ethanol in fuels also increases the potential formation of ground-level ozone. Exceeding the acceptable concentration of said contaminant can increase negative impacts on the environment and public health, particularly in metropolitan zones.

4.2 Incompatibility Issue

Ethanol is highly corrosive. In an old vehicle that lacks ethanol-proof components (pipes, seals, pumps), it eats away at rubber seals, plastic parts, and metal fuel lines. For the common person, this meant a high risk of sudden fuel leaks, broken fuel pumps, and expensive engine repairs.

Ethanol has lower energy density than petrol, meaning vehicles consume more fuel to travel the same distance, increasing costs. Ethanol's low cetane number causes poor ignition, engine knocking, power loss, and fuel separation.

4.3 The Biggest Winner Wasn't the Environment, But an Ethanol Industry.

The effort for blending created a guaranteed, subsidized market for sugar mills and ethanol producers. They received stable prices and offtake guarantees (long-term sales contract or production purchase commitment) from oil marketing companies. This was less about cleaning up the transport system and more about addressing the sugar industry's problems—managing surplus sugar, ensuring timely payments to farmers, and generating a new revenue stream.

The policy succeeded in benefiting a specific industry under a green banner, while the promises made for environmental transformation remained questionable.

4.4 Food vs. Fuel Crisis

Utilizing prime agricultural land and water to cultivate crops for fulfilling fuel needs in a water-stressed country raises a major ethical question. Critics warned of diverting food resources for energy, potentially driving up food prices and food insecurity. It exposed the conflict of priorities: energy security for vehicles versus food security for people.

Were we prioritizing fuel for cars over food for people?

Conclusion

Manufacturing an EV currently emits more than manufacturing a petrol car. It starts with a carbon debt.

Yes, in many cases today, an EV can feel like an “additional” vehicle rather than a perfect substitute, especially in growing markets. However, over its full life, it is almost always a lower-emission option. And crucially, it is the only technology we have that can become truly zero-emission as the electricity grid cleans up. A petrol car will always burn fuel.

The real shift in thinking we need is this: An EV is not a silver-bullet miracle product. It is a critical tool that only works as part of a larger system. For EVs to be the true environmental solution we hope for, three things must happen simultaneously:

- The Grid must go Clean and Green. (Renewable energy revolution).

- The Economy must go Circular. (Battery recycling revolution).

- EVs must genuinely replace, not just add to, ICE vehicles. (This requires strong policies, better infrastructure to alleviate range anxiety, and changed consumer behaviour).

The ethanol experiment is a clear warning. It shows us what happens when a "green" solution is promoted without fixing the whole system:

- It can damage what people already own (car engines then, batteries and grid stability now).

- It can fail its main environmental job (dirty air then, coal-powered EVs now).

- It can become more about business rather than change (helping sugar mills then, helping auto & battery makers now).

When a new "green" product is pushed, we must ask two tough questions:

- "Is this breaking the old system, or just adding a new layer on top of it?" (Like adding ethanol to a petrol system, or adding EVs to a coal grid).

- "Who is cashing the biggest cheque?" Is it the environment and the public, or is it a select group of industries?

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit science journal provides scientific awareness and climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About the author

Daksh Mishra

The Founder and Editor

Daksh Mishra is a Chemical Engineering undergraduate at National Institute Of Technology (NIT) Allahabad (India) and the founder-editor of an independent science journal focused on climate change, sustainability, and energy systems. His articles emphasise systems-level analysis and evidence-based scientific communication.

Reference

- Harde, Chaitanya Kaduba, and Deepak Kumar Ojha. “Are Ethanol-Gasoline Blends Sustainable in India? A Life Cycle Perspective on Benefits and Trade-Offs.” Sustainable Chemistry for Climate Action, vol. 7, 29 Sept. 2025, p. 100128, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772826925000732, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scca.2025.100128.

- “Why Will Electric Vehicles Benefit India Irrespective of New Power Sector Policies? - International Council on Clean Transportation.” International Council on Clean Transportation, 29 Sept. 2021, theicct.org/why-will-electric-vehicles-benefit-india-irrespective-of-new-power-sector-policies/.

- R B, Lakshmi. “The Environmental Impact of Battery Production for Electrical Vehicles.” Earth.org, 11 Jan. 2023, earth.org/environmental-impact-of-battery-production/.

- NITI Aayog & BCG (2022), Promoting Clean Energy Usage Through Accelerated Localization of E-Mobility Value Chain.

- NITI Aayog (2025). Unlocking a $200 Billion Opportunity.

- “Additional Resources -.” Acela.org, 2 Sept. 2020, www.acela.org/resource/additional-resources/

- Ember (2025). From Fossil to Flexible: Advancing India’s Road Transport Electrification.

- Down To Earth (2023),Coal-fired electricity used for charging EVs in India defeats the very purpose of clean energy.

- Transport & Environment, Ethanol’s emissions gap in India (2022).

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), Lifecycle GHG emissions of ethanol in India (2020).

- International Energy Agency (IEA), Global EV Outlook (2023).

- Patil, Abhijeet. “Stop Discrimination in Ethanol Procurement, Pvt Sugar Millers Urge Govt.” The Times of India, The Times Of India, 19 Sept. 2025, timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolhapur/stop-discrimination-in-ethanol-procurement-pvt-sugar-millers-urge-govt/articleshow/124003787.

- “Concerns on 20% blending of ethanol in PETROL and BEYOND.” Pib.gov.in, 2025, www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2155558®=3&lang=2.